Works created for this research:

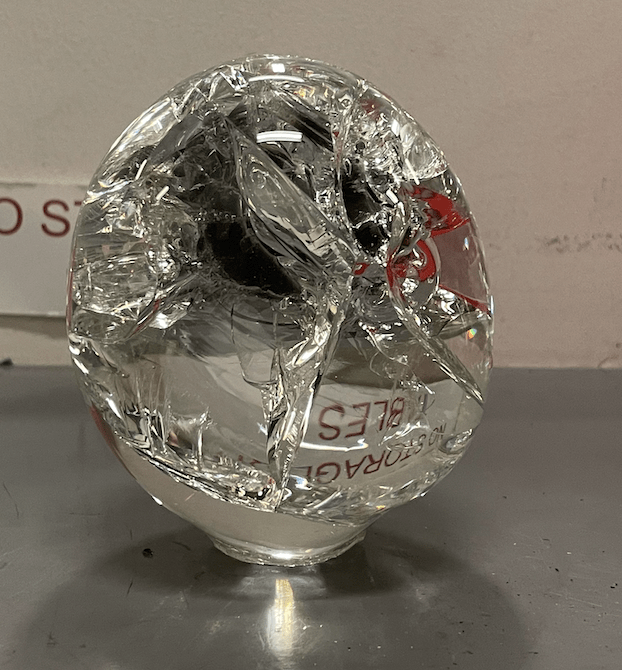

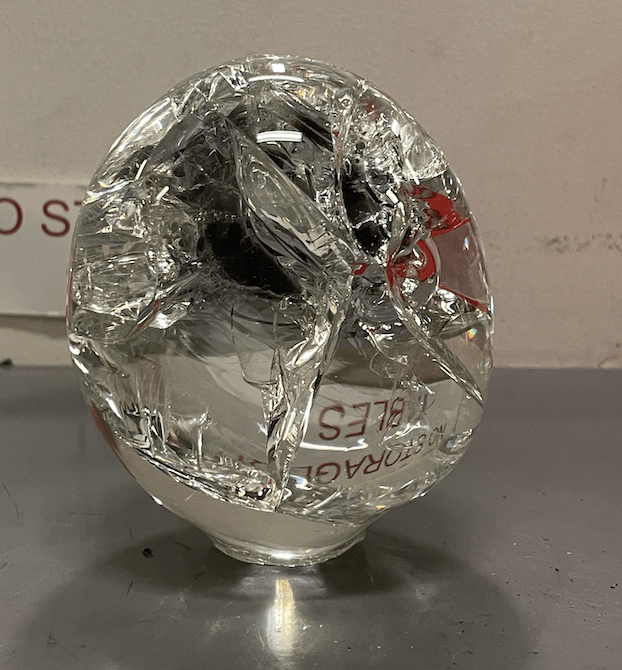

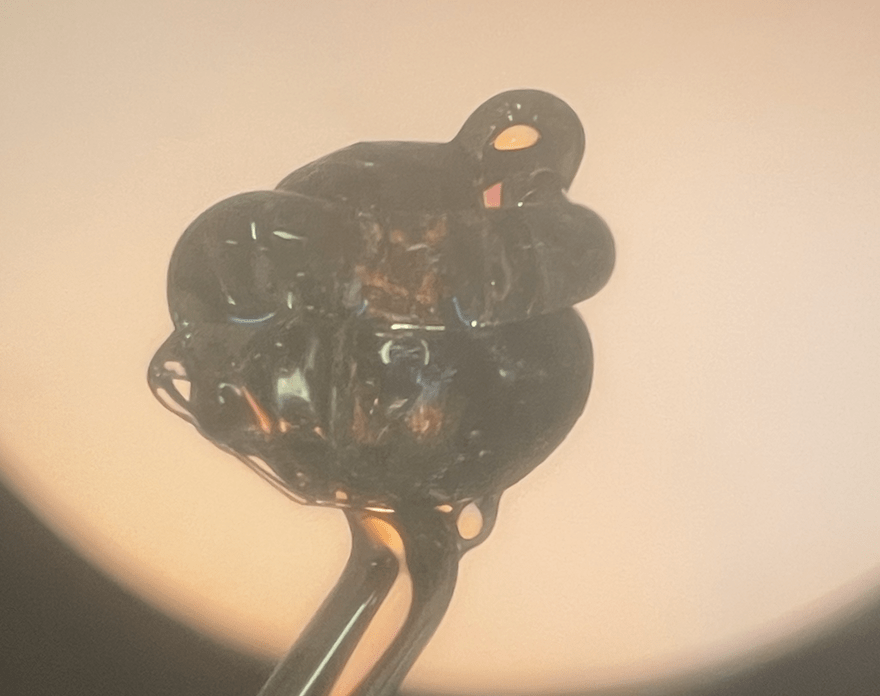

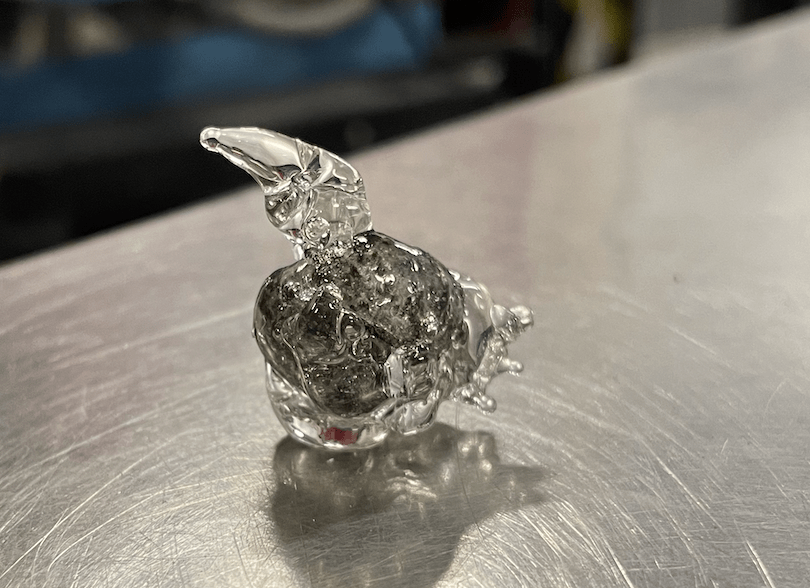

I experimented with both hot-blown and flameworked glass for this project to see how the compatibility of soft glass/hard glass and obsidian would appear through cracks in each type of glass. This is also an experimentation of different amounts of heat the obsidian is exposed to. The hot blown glass is also at a much larger scale than the flameworked glass, which creates an interesting contrast between the pieces.

I am interested in the question of why glass artists do not use obsidian in modern glass techniques when it is a type of raw glass found all over the world, and some of the most ancient glass that exists. This is important given the current state of increased research, interest, and art generated by scholars and artists respectively honoring Indigenous cultures and artists in North America, such as the Cuevas family who are the creators of the Taller de Obsidiana (an obsidian and glass Atelier in Mexico), and research presented by Alejandro Pastrana and David Carballo in their article for material intelligence, “Obsidian in Mesoamerica”. Additionally, this is important given the current crisis of division that exists between art and science, which inhibits and restricts innovation, as stated in “Using obsidian in glass art” by Professor Fabian Wadsworth and others. My thesis, therefore, offers an innovative perspective and solution to the question of how glass artists can use obsidian with modern glass techniques by combining the methods of contemporary glassworking and ancient symbols and ideas. Furthermore, the ancient glassworking/obsidian techniques demonstrated in Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas display the many uses for obsidian in Mayan civilizations, and how the trade of obsidian represents a larger global importance of the material because of how valued it was in ancient times. I had previously not thought about the importance of luxury goods for this project, but, as this source has made clear, luxury obsidian goods represent important aspects of these societies such as religion, military, and artisan pursuits of the ancient Americas. Lastly, by rethinking the colonial history of obsidian as stated in “The Mirror, the Magus and More: Reflections on John Dee’s Obsidian Mirror” using modern scientific developments to address and critique material appropriations of obsidian in colonial contexts, we can understand the time of early colonization more deeply to deconstruct imperialist ideas in Westernized art mediums like glass. This overall historical approach brings a deeper understanding and appreciation for obsidian as an artistic and scientific material and demonstrates the importance of interdisciplinary research/projects.

In my paper, I support the validity of this interdisciplinary approach through a three-part analysis of obsidian and glass making. In section one, I explore how modern scientists and artists take inspiration from various sources in order to use glass and obsidian. In “Using Obsidian for glass art”, the authors advocate and encourage glass artists across the world who use obsidian to create art, and the methods they use, which I have used somewhat as a guide for my own research and artistic endeavors. I agree that interdisciplinary approaches are necessary and that artists and scientists should collaborate more, however, after working with both for this project, I believe that a common language between the two needs to be developed in order to foster this connection. For example, a term used in glass is off-gasing, which is when an artist heats a glass material and allows it time to release impurities. This is similar to volcanic ideas of degassing, which is where a volcano releases volatile gas from its magma. By recognizing that these concepts are similar, scientists and artists can work together to find more interdisciplinary connections to inspire art creation and scientific research. Through these conversations, more questions can arise, and lead to practitioners looking for more nuanced answers and/or sources for research. Additionally, many of the other scientific sources utilized for my research were somewhat inaccessible to an undergraduate student like myself, which required lots of outside and research, like the article “Obsidian”, which was generously provided by Professor Wadsworth. However, even within the realm of the social sciences and practical sciences, there are debates on how to integrate the two, as shown in “Prospects and pitfalls in integrating volcanology and archaeology: A review”. While this article points to funding and siloing of academics as a big hurdle, I believe that the issue begins even earlier, when young students are taught to excel in one area or major in college, or in some places, as early as high school.

In section two, I then examine the history and materiality of obsidian from the perspective of those who made the objects and the historians and archaeologists who study these cultures in the present through the lens of the colonial and institutional gaze. I focus heavily on the example of John Dee’s Obsidian Mirror because this object, as asserted in the article “The Mirror, the Magus and more: Reflections on John Dee’s obsidian mirror”, is an important source to understand how colonial powers, such as Spain and Britain have spun narratives around stolen objects by categorizing this obsidian mirror as a European object in the British Museum, rather than one of the Americas because of its provenance of John Dee, a British figure. While I agree that this article does a good job of explaining how the artifact got to the British Museum using provenance, I believe that it lacked a rejection of colonialism, and how the misattribution of objects to different regions impacts the way Mesoamerican obsidian objects are understood and appreciated by the general public. Furthermore, returning to the article, it does not explicitly mention whether the object was “stolen”, or how colonizers treated obsidian artisans during early colonization, which is a pitfall to this source. However, the use of new technology to locate the exact region where this obsidian mirror is from in Pachuca, Mexico, definitely strengthened the author’s arguments and made more clear the harms of placing this mirror in the European section of the museum away from its siblings also made from the same region in Pachuca in the Americas section of the museum.

Finally, section 3 demonstrates how the study and artistry of obsidian and glass can be expanded if we use knowledge about volcanic and earth sciences to create nuanced pieces of art that can be beautiful, educational, and meditative. In this section, I focus on the art created by the Cuevas family In “Negro Como Mi Corazon”, who utilize obsidian in their artworks, and then I explore my own experimentation and research to build upon these artists and scientists’ works. This article celebrates Cuevas’ inventive use and minimalist approach to obsidian artwork for profit, and ‘letting go of prehistoric legacy’. The article does not explain really what this means, however, examples of artwork the family creates include a minimalist Mickey Mouse sculpture of raw obsidian, polished obsidian and gold to celebrate an anniversary of the Mouse’s ‘birth’, which could indicate that the release of legacy involves art creation for colonial powers and capitalists, such as the Disney Corporation in the United States. Yet, at the same time, one of the artists in the article discusses how ancient mythology has complicated the way he views obsidian as similar to a human heart. This blending and splicing of “letting go of a legacy” while also constantly referencing pre-colonial Mexico is confusing, and made me question the perspective of the author, and these artists about legacy, art creation, and colonialism.

Methods/Hypothesis

I hypothesize that obsidian can be used in flameworking as a frit, by heating the material in a crucible twice, the first time to release water, and the second time to stabilize the structure. This process takes many hours and is somewhat difficult to do because it requires a certain kind of kiln to complete, which is why I believe it is not done often. I also believe it is not used because it is a sacred material to many cultures, such as those from the Easter Islands , and across Mesoamerica, which means it crosses ethical boundaries for artists outside of these cultures, such as myself, to use this material. Obsidian can also be incredibly dangerous to work with, as it can be sharpened to points that are sharper than steel, and can be used/still is in some places for surgical procedures. Furthermore, within my experience of working with obsidian, it can be a very temperamental material to work with that can only be exposed to a direct flame in small amounts to reduce the likelihood of fracturing or exploding, which greatly limits what I can make. This material is also extremely impure, which causes it to react negatively with pure glass like soft glass or borosilicate, which causes these objects to break over time, if not immediately.

Additionally, I believe that by utilizing a lampworking torch to heat, devitrify, and release water from the obsidian in a single step, this will make the obsidian workable wigh borosilicate glass for further use. I believe that because the temperatures for annealing obsidian and borosilicate glass (over 1500 degrees Fahrenheit and 1050 degrees Fahrenheit respectively) are so different, it is likely that annealing the obsidian for extended periods of time will not increase the stability and risk of fracture at the same rate as for borosilicate glass. Therefore, I believe that the art and scientific pieces I create will have some type of expiration date, and will break at some point. Therefore, the art and process of destruction must be at the core of my pieces to reflect this. This is also thematically and materially relevant to obsidian because of its creation in a volcanic setting, which is often destructive and temperamental, thus connecting the obsidian and pure glass to its earth science origins.

Lastly, I believe that obsidian, as proven by Mayan artists and others across the world, can be cold-worked, sanded, and polished, despite the difficulty of using the material which can prematurely fracture under stress. This fracturing can happen when pressure is applied to obsidian, which is unstable and can contain trapped air bubbles or stress depending on how it was heated and cooled. As all obsidian is created differently because it comes from a volcano in different regions, conditions, chemical impurities, and silica concentrations, this makes working with obsidian incredibly difficult, even when coldworking it and not adding any heat. I believe that using a polariscope can help find the stress on thinner pieces of obsidian to make working with it more predictable. This is because a polariscope can reveal the stress in transparent objects as light shines through the object. Furthermore, because obsidian fractures concoidally, one can more often than not find where obsidian will fracture/the direction it will fracture in, and use this knowledge to work with the material. Therefore, it will be easier to sand and polish these pieces using this technology and other modern sanding techniques as compared to ancient times, before the invention of the polariscope.

Research/Background

In the work, “Using Obsidian in Glass Art Practice”, by Fabian Wadsworth et al, the authors explore how obsidian can be used in contemporary glass making and using modern glass technology. The authors discuss how different artists have used obsidian in their work and their creative processes. Then, the authors explore the scientific and physical ways in which artists manipulate obsidian to create different kinds of artwork. They also delve into the scientific principles of obsidian melting and explicitly discuss how this can be done in a glass studio. This article has served as a guide for me to use in order to heat obsidian to make it workable with the type of glass I would like to use, by melting it twice. The first time the obsidian is heated in a crucible, which then becomes a “highly vesicular, porous glass”, and bubbles up, which leads it to look somewhat like house insulation. Then, the second time it is heated and crushed up, it looks more similar to reflective glass. From there, it can be crushed into a frit and used in a kiln with soda lime/soft glass, as demonstrated in the piece PEDM.

There are many kinds of glass, but the one discussed in this article is mainly soda lime glass, which is a much softer, more fragile glass that flows and melts at a lower temperature than obsidian. One shortcoming of this essay is that the authors do not have examples of art from flameworkers, or with borosilicate glass, which is a type of glass that the authors remark is similar in viscosity and temperature tolerance to obsidian. Borosilicate glass is also known as “scientific glass” used for beakers and other scientific equipment, and for its popular usage in Pyrex cooking materials because of its ability to withstand extremely high temperatures, and its relative durability to other types of glass. Borosilicate is also interesting because it can be reheated and worked on, while softer glasses cannot be remade or reworked after it has been annealed because it is a more fragile and sensitive material. This is partly why I chose to work with borosilicate and flameworking, to expand upon this research, and hopefully gain more insight into how obsidian reacts with borosilicate glass.

Another aspect of this article that inspired me is the way the authors praise and highlight the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration between scientists and artists to bring deeper understandings to both fields. Through collaboration, more knowledge can be gained, and a larger sense of community is established. Furthermore, the authors remark on the similarities between glass workers’ kilns and early volcanologists’ kilns, which serves as a reminder of how technology can be utilized for various groups of people, but when they are siloed in academia, this can stymie progress and knowledge. The authors also hope that we can “transform the scientist”, which, during a time of a vast disconnect between science and the general public, would be a necessary change to help give more trust between both groups.

The importance of an interdisciplinary perspective when undertaking projects of volcanology is extolled by Professor Karen Holmberg, in the work, “Prospects and pitfalls in integrating volcanology and archaeology: A review”. The authors seek to understand how volcanology and archaeology are sometimes at odds with each other, why this is, and how this issue can be solved for a greater understanding of the past and present volcanic activity. The authors point to issues with funding, journal publications, and education as major factors for this discrepancy, but credit conferences and other points of contact for researchers to go outside their siloed disciplines. The authors conclude that “Bringing together the natural scientific excitement and acumen of volcanology with the affective and narrative expertise of the humanities/social sciences in general and of archaeology, in particular, offers a powerful alliance in producing and disseminating the knowledge needed for the Anthropocene” (Riede, Holmberg et al p.9). This is exactly what my project seeks to do through utilizing art and obsidian as a means of creating, understanding, and communicating knowledge about earth science for audiences in the Anthropocene.

In order to understand obsidian as a cultural material, I focused on obsidian objects from Mexico and North America because that is where my obsidian came from. In the source, “The Mirror, the Magus and More: Reflections on John Dee’s Obsidian Mirror”, the authors explore John Dee’s Obsidian Mirror, which is currently located in England, to understand how objects can be imbued with different meanings over time. This article mainly focuses on how meanings of objects change because of colonization, and what it means for something to “belong” to a culture or region. The authors begin with the Aztecs, who made the object during early colonization by the Spanish. This object then travels across Europe, to John Dee, and later the British Museum. They highlight how an object, a mirror and a material, can change through these different cultural contexts, and colonization and imperialism should shape how modern viewers and curators categorize and contextualize objects.

The authors explore John Dee’s history as a Tudor figure and magician who used the mirror to call upon angels. In the late Renaissance, the authors of this paper remark that this mirror “symbolizes entanglement between science and magic” (Campbell et al). Then, the authors reconstruct the Provenance of the mirror, which they believe Dee could have purchased during Kunstkammer in Bohemia, a European cabinet of curiosities or proto museum. By discussing the Kunstkammer, the authors reveal how New World artifacts were treated at this time, and how a fascination, or fetishization, of other cultures has transcended time. However, it makes readers question how these objects ended up in these places at all, and what ideas of ownership and appropriation mean in this context. The Mirror changed hands four times before going to the British Museum in 1966, where it is placed in the Britain, Europe, and Prehistory Sections of the museum, rather than the Americas section of the mirror’s origin. This article was helpful in situating the conflict of an object that became important in British history but was likely stolen from its original context in the Aztec empire. This section raised important questions for me about what it means for me, a white settler, to make art using obsidian on stolen land.

In my own experiments, I utilized new technologies in order to experiment with obsidian, such as a miniature glory hole which I discuss later. Additionally, I was lucky to be able to utilize furnaces at Columbia University Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in collaboration with Karen Holmberg and Yves Mousallam to melt obsidian and borosilicate. Through this experimentation, I was able to foster interdisciplinary connections between scientists and artists and use equipment designed for scientific purposes for artistic ones. I wonder if this is at all similar to the appropriation John Dee and the British Museum have done, or if this is a more positive appropriation or usage of obsidian. This article demonstrates the complicated interplay between different groups through objects and materials, such as the Obsidian Mirror. It also demonstrates how new scientific technology can influence our understanding of obsidian objects, and create new geographic timelines for objects. The influence of new technology inspired me to look at innovations and technological changes within the world of glass that could be applied to my own experiments and artwork.

The authors of the John Dee article then explore how obsidian was used for military, domestic equipment, and religious ceremonies for the Aztec civilization. These uses are expanded through other sources I looked at, such as Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas. The book chronicle the hundreds of years of artwork created in Mexico by the Aztecs and other groups, and how different materials, like obsidian, were shaped and used to signify different things throughout different cultures and time periods. The Aztecs associated obsidian with different deities, such as Tezcatlipoca, whose name means “smoking mirror”, who was the god of War, Night, and Sacrifice. They also remark that toward the end of the Aztec empire, obsidian was controlled by elites and worked by “tezcachiuhqui”, who were obsidian specialists at the time. The authors also discuss the complexity of navigating the time period of the end of the Empire, the beginning of Spanish colonization, and how these mirrors came to be. Early colonization is historically difficult to navigate because of the fall of the Aztec empire, and reconstructing this political and violent/genocidal history is difficult. For example, Spanish missionaries used the mirrors as portable altars, and during colonization by Cortes, some mirrors and objects were commissioned by the Spanish, which is documented by Friar Bernadino de Sahagún, a Spanish missionary whose journals are heavily used in reconstructing early Spanish colonialism (Campbell et al).

From this research, I became curious about modern obsidian workers and artists’ view the materiality of obsidian, and what they create. In “Negro Como Mi Corazon”, by Amanda Forment, the author explores Taller de Obsidiana, a family-owned obsidian atelier founded in 2014 by brother and sister Gerardo and Topacio Cuevas that uses traditional and contemporary glass/obsidian techniques to create art. The pair’s grandfather began a lapidary practice specializing in obsidian in 1957, recreating archeological findings found in the Teotihuacan Valley. The author defines the art style of each generation of the Cuevas family while weaving their stories together. The author then explores how difficult obsidian can be to work with, and how the Cuevas siblings came to work with the material even though they did not want to become obsidian artists. However, their beliefs changed as they began to discuss ideas with their father, who utilized his wisdom in their art design process today. Then Gerardo states “‘We design like our dad, we like geometry, we let go of the prehispanic legacy’” (Cueva qt in Forment). This led me to question what this means, and what letting go of “prehispanic legacy” means. This also was an interesting article to read because of how entrenched in family history the obsidian is for these artists, yet the pieces highlighted in the article are a dedication to Mickey Mouse, and an obsidian wall, which is a tribute to the pyramid of the sun and the moon of Teotihuacan. It is a unique blend of different cultures’ idols; Mickey Mouse and a dedication to an ancient god and culture. Is this what it means to let go of the prehispanic legacy?

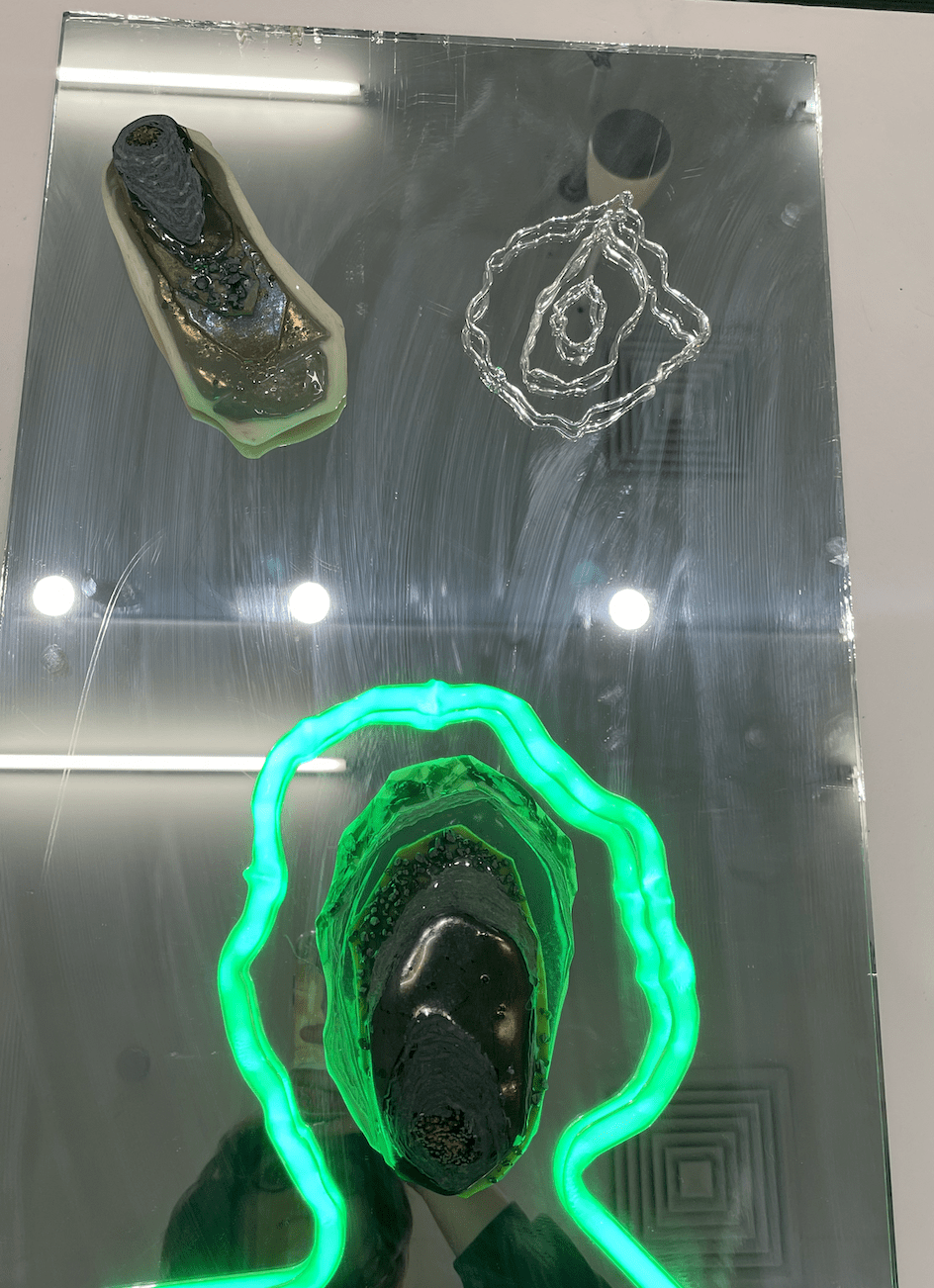

This wall also features a neon sign which reads in white “negro como mi corazon” (translated to “as black like my heart”). Neon is a complicated art form that is associated heavily with capitalism because of its use as advertisements and sign-making (Lees). However, there are many artists now who reject this connection, and utilize neon for sculpture, devoid of capitalistic endeavors, for purely art and experimental purposes. I hope to one day create a neon tube made of obsidian, and to utilize neon with obsidian to create contrast between light and darkness; aliveness and deadness. Returning to Forment’s essay, it ends with a beautiful paragraph explaining that in the Popol Vuh, a foundational text for the Maya, humans were said to be made by the gods out of Maize. Gerardo says, “‘if our skin is made of corn, why not? Our heart is made from obsidian. It is hard, yet fragile, like the human heart’”. This quote gets at the core of my glasswork; Obsidian is more than a volcanic byproduct, there is something inside of it that is compelling about the human condition. There is something compelling about humans ability to look at impure and imperfectly formed materials, like obsidian, and see something inspiring and beautiful that I hope to convey in my art.

Results

In my own experimentation with obsidian, to start my practice I crushed the obsidian into 1 mm-5 cm chunks. Some I crushed further to become a powder, which makes the obsidian look more gray/white than the black color it is in a large chunk. Crushing the obsidian was beautiful because the way it fractures conchoidally shows how it was melted in the volcano’s magma, which I learned more about through Professor Wadsworth’s other study in “Obsidian”. After crushing the obsidian, I put the pieces on a graphite sheet, which is used in flameworking and lampworking to press frit into glass. Then, I heated up clear pieces of borosilicate glass, and pressed obsidian chunks into it. Then, I would increase the flame heat to be as hot as possible, which causes the obsidian to boil. Boiling obsidian is incredibly beautiful because the bubbles of water gurgle out of the glass. However, I do not believe the obsidian completely melted because it would not melt enough to stretch or mix with the clear glass. I created a small obsidian and borosilicate glass heart inspired by Gerardo’s words, and I hope to create a larger version someday.

I believe as I get better as a flame worker, I will become better at melting the obsidian at a high heat because the borosilicate melts at a lower temperature so trying to balance both was difficult. Sometimes, the boro would melt much faster than the obsidian, which would cause the obsidian/borosilicate blob to melt off. Some of the early blobs that were not annealed would fracture conchoidally, just like obsidian. I began experimenting with different borosilicate color glass to see if it would be more compatible with the obsidian. Additionally, I experimented with layering the borosilicate over each level of obsidian frit, rather than adding obsidian only; this encases the obsidian and makes it a bit easier to shape, as the borosilicate is being shaped, rather than the obsidian which does not stretch as much. This idea was suggested to me by Jess Krichelle, an incredible flameworking and neon teacher, who has been essential to the success of this project and has continued to inspire me through flameworking and working with borosilicate. Each blob that I made was then cooled for about 20 minutes. I have been experimenting with annealing temperatures as well, but so far the non-annealed borosilicate obsidian glass has survived and does not seem too much more fragile than the annealed pieces (this could be proved untrue over time, which is something I will continue to survey). Additionally, there are many different types, formulas, and brands of borosilicate glass that can anneal at different temperatures, similar to obsidian, but it is more uniform than obsidian overall in its chemical structure and stability. This is a testament to how borosilicate glass is much less sensitive than soda lime glass, and part of why I chose boro for this project.

After all this, I looked at the glass through the polariscope to reveal where the stress in the glass is, and whether or not the areas with obsidian presented more stress. All glass has stress, regardless of whether it has obsidian or not, so it is difficult to draw a conclusion on exactly what amounts of stress the obsidian added to the glass. The stress can be lessened through longer annealing times, which I will continue to experiment with. Because the annealing and melting points of borosilicate versus obsidian are different, this will take a long period of experimentation and learning, beyond the scope of this project, to find the perfect annealing temperature for these pieces. Additionally, every piece of obsidian is unique and can have different heating points, so because of this instability and variation, making generalizations about the way each piece of obsidian reacts is difficult. This is reflected by Professor Wadsworth et al s article, which states, “The diverse types of obsidian (Fig. 1; Table 1) reflect varied conditions and environments in which quenching of silicic magma can form a crystal- and bubble-poor glass” (Wadsworth et al). Working with obsidian has proven to be challenging because of the diversity of obsidian. Moving forward, I believe it would be worthwhile to experiment with quartz glass, the hardest and most difficult to melt glass with obsidian because they would likely have a similar melting temperature and viscosity. However, quartz glass takes many years of skill to work with and has an extremely high silica content, which might make it more compatible with obsidian. Quartz glass is also much more expensive and must be melted in extremely specific ways that are not accessible to most artists or studios.

Next, I worked with a mini glory hole. The obsidian is placed on the refractory material/bottom of the glory hole, which holds incredibly high heat without breaking. The obsidian was stretched from there, using the refractory material to anchor the obsidian down, and pulling with tongs. The obsidian reacted more to the heat of the refractory material rather than the direct flame. I also learned that degassing the obsidian (exposing it to heat, letting the water boil out, allowing it to sit for around 20 minutes, and then reheating it slowly) provided more stable glass that did not shatter or crack when dropped from 1 foot in the air. Other drop tests using borosilicate and obsidian did fracture, which indicates that these materials are either incompatible together, or the obsidian was too unstable when encased in borosilicate glass. However, the obsidian that survived drops encased in borosilicate showed little to no stress under the polariscope, whereas the obsidian exposed to direct flame showed more stress. Inside the miniature gloryhole, the obsidian stretched and was incredibly viscose, which had not happened with exposure to direct flame. Additionally, the obsidian seemed to lose mass from this experiment, so I decided to record the masses of obsidian before and after degassing, and then after stretching. The obsidian also changed color when touching the metal tongs to a red color, likely as a result of the exposure to iron in the metal.

I am still experimenting with making the obsidian stretch and melt through additional experiments, and adding more steps to crushing the obsidian. For example, as detailed in “Using Obsidian for Glass Art” by Professor Wadsworth et al, for the PEDM piece, I would like to try heating the obsidian twice to get rid of the water and gas, and then make it more stable. However, I am unsure if this process is only necessary for making obsidian compatible with soda lime glass, and if making it compatible with borosilicate requires fewer steps. I would also like to experiment with melting borosilicate in a kiln, which is not often done because of its significantly higher melting temperature, and its lack of use for artistic/kiln-made pieces.

I began with small bird shapes to shape my pieces because of my borosilicate skill level. A bird is relatively easy to do, but I would like to create rabbit shapes, in reverence and respect to Mayan artists of the past, who used obsidian as art and religious artifacts. Specifically, in artifacts depicted in Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Maya Art, the book states, “the lunar Maize God was among a select group of deities who were consistently depicted on incised obsidian flakes placed in caches (ritual deposits hidden beneath floors… while sometimes described as a moon goddess, the young deity who holds a rabbit while sitting inside a lunar crescent on these flakes is clad in a simple belt and short skit, likely a male outfit, implying that the figure instead represents the lunar Maize god…. In mythical narratives, these little creatures [rabbits] are often tricksters” (Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Maya Art page 83). The rabbit became important. According to these authors, a lunar deity had a pet rabbit, or swallowed a rabbit, or the rabbit was punished and then thrown to the moon, or a god slapped a rabbit onto the moon. Regardless of these various sources, the rabbit is an important representation of the moon. This is significant for obsidian formation, because the moon was at one point in its geological history volcanically active, and has a high silica content. According to Paul D. Spudis, of the Smithsonian Magazine, there was “remotely sensed compositional data show that the lunar red spots are felsic domes of obsidian and rhyolite” in 2011, creating a further connection between these obsidian rabbits and the obsidian-littered moon.

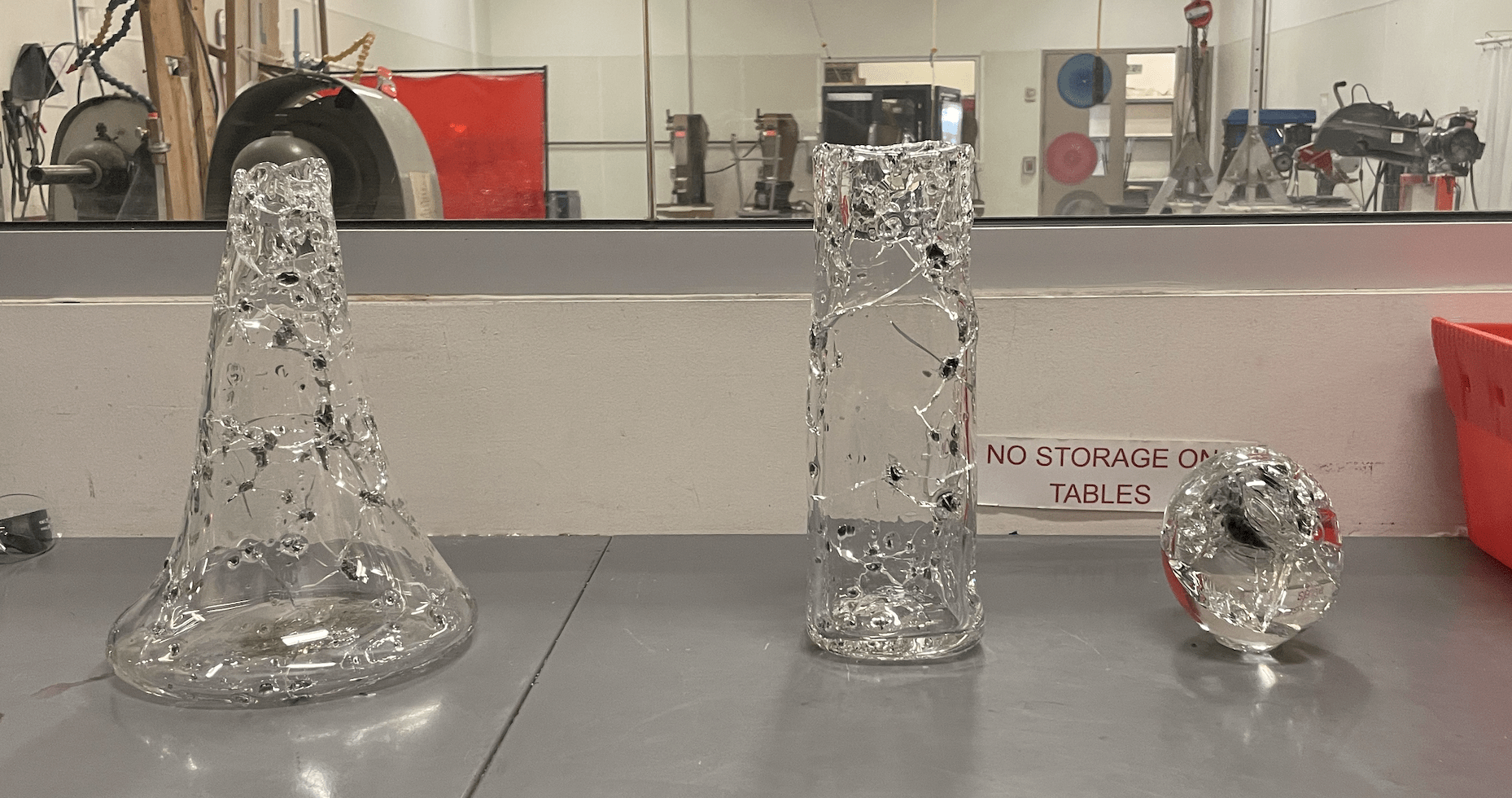

I then experimented with regular blown glass with devitrified and preheated obsidian pieces, to see if this could produce pieces that did not explode. I created two hollow and two solid pieces that still need to be polished. Working with obsidian in this setting was difficult because glassblowing is on a much larger scale than the flameworking I am capable of, so it was a lot of heavy lifting and physical activity. This part was only possible because of Aiyah Obaiah, who took the lead on this section of artwork because of her extensive glassblowing expertise. Of the hollow objects, we created a small volcano inspired by Krakatoa’s shape, and a rectangular prism shape, inspired by columnar jointing. Columnar jointing is a specific way that magma cools, making large basalt hexagonal columns that are found around the world in places such as Ireland, Wyoming, and many other places internationally.

During my time at Lamont-Doherty, I experimented with Professor Karen Holmberg and Yves Moussallam using borosilicate and obsidian. I wanted to blow a bubble using obsidian by melting the obsidian in their volcanology furnace and placing it in an obsidian crucible at over 1000 degrees Celsius. Unfortunately, the obsidian exploded in the crucible before it got hot enough to be moveable. However, I was able to utilize a hydrogen and oxygen torch, which was similar to a flameworking torch except this one was smaller and much hotter. In general, this torch is used for working with platinum. This torch was difficult to work with because the flame heated the borosilicate glass extremely fast. Additionally, because the flame was so small and concentrated it was difficult to heat everything uniformly. I asked the scientists in the laboratory to “play” with the obsidian and glass and helped them make art with the obsidian and glass. We made small glass marble shapes with obsidian inside. They said, afterward, that the lab would never feel the same again because we had made art there, which was exciting. It was such a new experience to have the scientists ask me what to do and see me as an equal. From this experiment, I learned that obsidian will likely never be viscose enough to completely move like glass, but it can stretch with enough heat to twirl and manipulate with borosilicate glass using an extremely powerful torch. I did learn a lot from this experimentation, and from asking both of these volcano experts about their thoughts on my project/research.

Conclusion

To conclude, obsidian is a material I will continue working with and explore other rocks and minerals in my glass practice. Professor Elaine Ayers’ article, “James Sowerby’s British Mineralogy (1802–17)”, discusses the work of scientific illustrator and naturalist, James Sowerby, and the implications of his work with geology and mineralogy in the 19th century. Professor Ayers states, “Rocks and minerals, in all of their mundanity, held [and still do] beautiful and sublime lessons about the world for specialists and non-specialists alike…”. The importance of the beautiful and sublime underscores this project of working with obsidian and glass. Obsidian and glass are materials that symbolize the duality of the sublime, as ambivalent substances that can either reflect and reveal or obscure. The fragility and simultaneous strength of obsidian speaks to the way that balance, nuance, and ambivalence are essential elements of the sublime and understanding of our world, especially in art practice. The sharpness of obsidian alludes to the transformative, and painful aspects of creating art and seeking knowledge. Both glass and obsidian encapsulate the intense complexity of the spiritual and the sublime, which are essential materials to create meaningful art.

Works cited:

Ayers, Elaine. “James Sowerby’s *British Mineralogy* (1802–17).” The Public Domain Review, publicdomainreview.org/collection/sowerby-mineralogy/. Accessed 22 Aug. 2023.

Campbell, S., Healey, E., Kuzmin, Y., & Glascock, M. (2021). The mirror, the magus and more: Reflections on John Dee’s obsidian mirror. Antiquity, 95(384), 1547-1564. doi:10.15184/aqy.2021.132

Lees, Kacie. ‘Neon Primer: A Handbook on Light Construction’. Plazma Press. 2021.

Felix Riede, Gina L. Barnes, Mark D. Elson, Gerald A. Oetelaar, Karen G. Holmberg, Payson Sheets,

Prospects and pitfalls in integrating volcanology and archaeology: A review, Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, Volume 401, 2020, 106977, ISSN 0377-0273,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2020.106977.

Amanda Forment. Negro Como Mi Corazon featured in“Obsidian.” Material Intelligence, 17 June 2023, http://www.materialintelligencemag.org/obsidian/.

Spudis, Paul. “Exotic Volcanoes on the Moon.” Smithsonian.Com, Smithsonian Institution, 3 Aug. 2011, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/exotic-volcanoes-on-the-moon-42542301/.

Pillsbury, Joanne, Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos, and James A. Doyle eds. Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Maya Art. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.

Pillsbury, Joanne, Timothy F. Potts, and Kim N. Richter, eds. Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017, no. 143, p. 221.

Tuffen Hugh, Flude Stephanie, Berlo Kim, Wadsworth Fabian and Castro Jonathan. (2021). Obsidian. In: Alderton, David; Elias, Scott A. (eds.) Encyclopedia of Geology, 2nd edition. vol. 2, pp. 196-208. United Kingdom: Academic Press.

Wadsworth, F. B., Llewellin, E., Rennie, C., Watkinson, C., Mitchell, J., Vasseur, J., Mackie, A., Mackie, F., Carr, A., Schmiedel, T., Witcher, T., Soldati, A., Jackson, L., Foster, A., Hess, K.-U., Dingwell, D. and Hand, R. (2022) “Using obsidian in glass art practice”, Volcanica, 5(1), pp. 183–207. doi: 10.30909/vol.05.01.183207.